Note: this tutorial assumes you’re familiar with pinyin and basic Chinese characters.

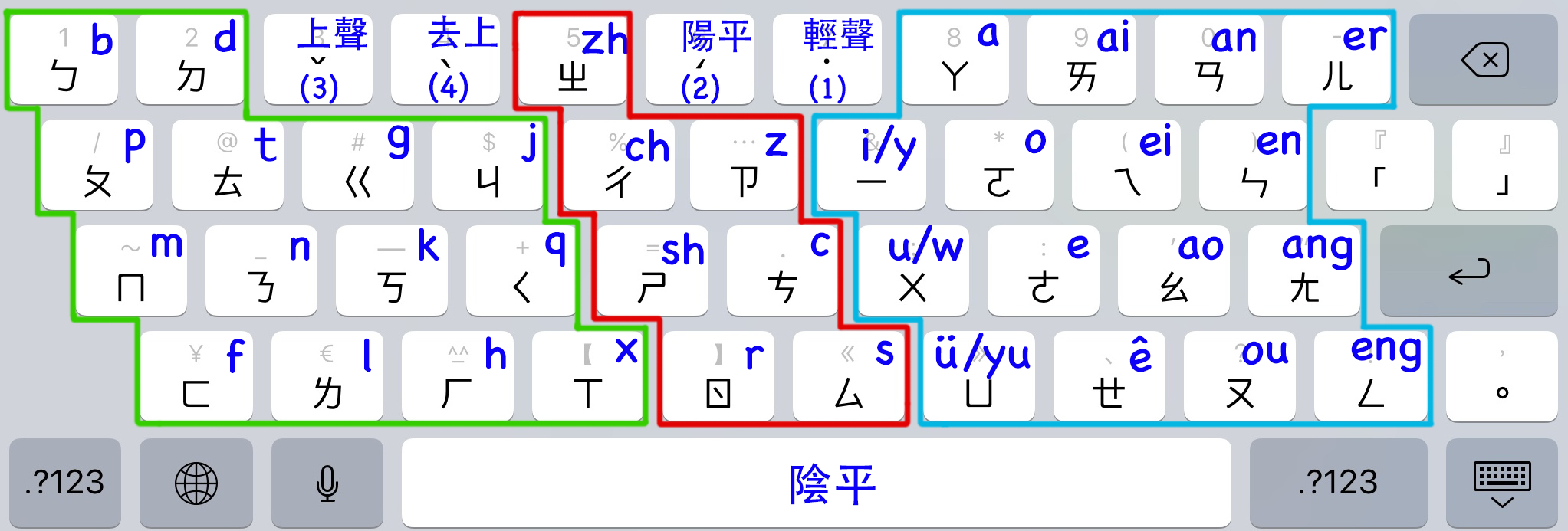

Now it’s time to learn 注音! Check out this table we made for you:

As confusing as it might seem at the first sight don’t worry, it’ll take only a couple of days to learn. Use this image as a reference, save it somewhere so it’s accessible within a few seconds – you will need it a lot in upcoming few days (in case of PC you can just set it as a wallpaper).

Some of those symbols are very easy to remember (if you know a decent number of Chinese characters), here’s a quick guide through them:

| Zhuyin | Pinyin | Trick to remember |

| ㄅ | b | Origin: from 勹, the ancient form and current top portion of 包 bāo |

| ㄆ | p | Origin: from 攵 which is a variant of 攴 (pū) |

| ㄇ | m | Can think of character 門 (mén) to remember the “m” sound |

| ㄈ | ||

| ㄉ | d | Origin: from ancient form of 刀 (dāo) |

| ㄊ | t | this one looks a lot like the English letter “t“ |

| ㄋ | n | Origin: from ancient form of 乃 (nǎi) |

| ㄌ | l | from archaic form of 力 (lì) |

| ㄍ | g | |

| ㄎ | k | Origin: from the archaic character 丂 kǎo, but it’s a lot easier to remember this character if you think of 考 (kǎo) |

| ㄏ | h | If you don’t know yet, the radical 厂 is pronounced as (hǎn) and that’s where the zhuyin character is from (you might’ve seen this radical in words like 原 (yuán)) |

| ㄐ | j(i) | Origin: from archaic character 丩(jiū), but it’s a lot easier to remember this character if you think of 叫 (jiào) |

| ㄑ | q(i) | |

| ㄒ | x(i) | Origin: from 下 (xià) |

| ㄓ | zh(i) | Origin: archaic form of 之 (zhī) |

| ㄔ | ch(i) | This one reminds me of 吃 (chī) |

| ㄕ | sh(i) | just think of 屎 (shǐ) |

| ㄖ | r(i) | it was made from an early version of 日 (rì) hence the sound is the same |

| ㄗ | ||

| ㄘ | ||

| ㄙ | s(i) | Think of 私 (sī) |

| ㄚ | a | from 丫 yā (the character means fork and looks like one) |

| ㄛ | o | |

| ㄜ | ê as in 餓 | |

| ㄝ | e as in 也 | Yeah, this one gives the “ye” sound and it derives from the character 也. I wish all zhuyin was this simple. |

| ㄞ | ai | the etymological background is the character 亥 hài |

| ㄟ | ||

| ㄠ | ao | Origin: from 幺 (yāo) |

| ㄡ | ou | Origin: from 又 (yòu) |

| ㄢ | an | Think of 安 (ān) |

| ㄣ | ||

| ㄤ | ang | From 尢 wāng |

| ㄥ | eng | Makes me think of 能(néng) |

| ㄦ | er | I don’t think this one needs an explanation |

| ㄧ | y(i) | Origin: from 一 (yī) |

| ㄨ | w/u | This one reminds me of 我 (wǒ), but its etymology is 㐅, which is ancient form of 五 wǔ (five) |

| ㄩ | yu/ü | Think of 曲 (qū) |

So how does it all work? Three different ways for different characters:

- You take a consonant from the green sector or and combine it with a vowel from the blue sector and then add the tone, example: ㄋㄧˇㄏㄠˇ 你好 (nǐ hǎo)

- Some of the consonants in green and red sectors work standalone ㄕˋ 是 (shì) – you do not need to explicitly add ㄧ (i) to it in zhuyin

- Some vowels also work standalone, ㄞˋ 愛 (ài)

An important rule to remember:

You never finish a word with a character from the blue sector. So, for example, you can’t write “nan” as ㄋㄚㄋ (n_a_n), you can only write it as ㄋㄢ (n_an)